Friends of mine have been house hunting. They visit prospective sites, and assess them for size and suitability: can they raise a family there? Does it meet everyone’s needs? Is the house sound and damp-proof?

When they have several options on the table, they debate.

Now, this is where things get a little strange.

The deliberation itself includes everything you might imagine from a robust conversation on housing, and each member has a say in the final decision, but it’s the method of debate I find most interesting.

They dance.

//

My friends are homeless, which further complicates matters. Things got too crowded where they’re from, and they needed to strike out and find somewhere new to live. There are a lot of them, too, thousands, in fact. This makes it challenging to come to a consensus, but miraculously, they do.

Several hundred of them are tasked with finding new digs. They have a shared vision of their dream property: it must be roomy and have good access; security is a priority. When the house hunters return, they dance their case before the community, and everybody votes. She who dances best, wins the heart of the collective.

//

These friends of mine are honeybees. An industrious matriarchal tribe that has taught me so much about community and, of course, dancing.

Swarm

I found a few thousand bees clumped on a willow branch several metres from the hive.

“You’re leaving me?” I asked.

It is so hard not to take it personally. The queen was among them, and the dance debates were in full flow. I imagined the hollow tree cavities they had found in the forest, or perhaps the bait hives of other beekeepers laced with lemongrass in the hope of catching a swarm.

I gave my limbs a shake, then presented my case – a new hive, I’ll build it myself, with winter insulation, lots of room and early morning sunlight. They watched me dance. The access is great, and I’ll narrow it in autumn to keep the mice out. Oh, and wait until you see the view.

They agreed to move in.

Queen Bee

I visited my hives this week to see if everyone had settled.

In the mother hive from which the swarm had absconded, a few thousand bees stayed behind to nurse brood. Before the other bees left, they drew queen cells from the wax, long peanut-shaped cocoons in which the larvae were exclusively fed royal jelly (a rich secretion from the glands of nurse bees).

How a bee is fed, determines what she becomes.

Of the eight queen cells they left behind, I kept one. The new queen hatched and left the hive for her mating flight. Somewhere above the hazel trees, the drones congregated, waiting to catch a virgin in flight. They chased her for miles. One by one, the weaker ones dropped off until he who stayed the course fathered every bee to be in my hive.

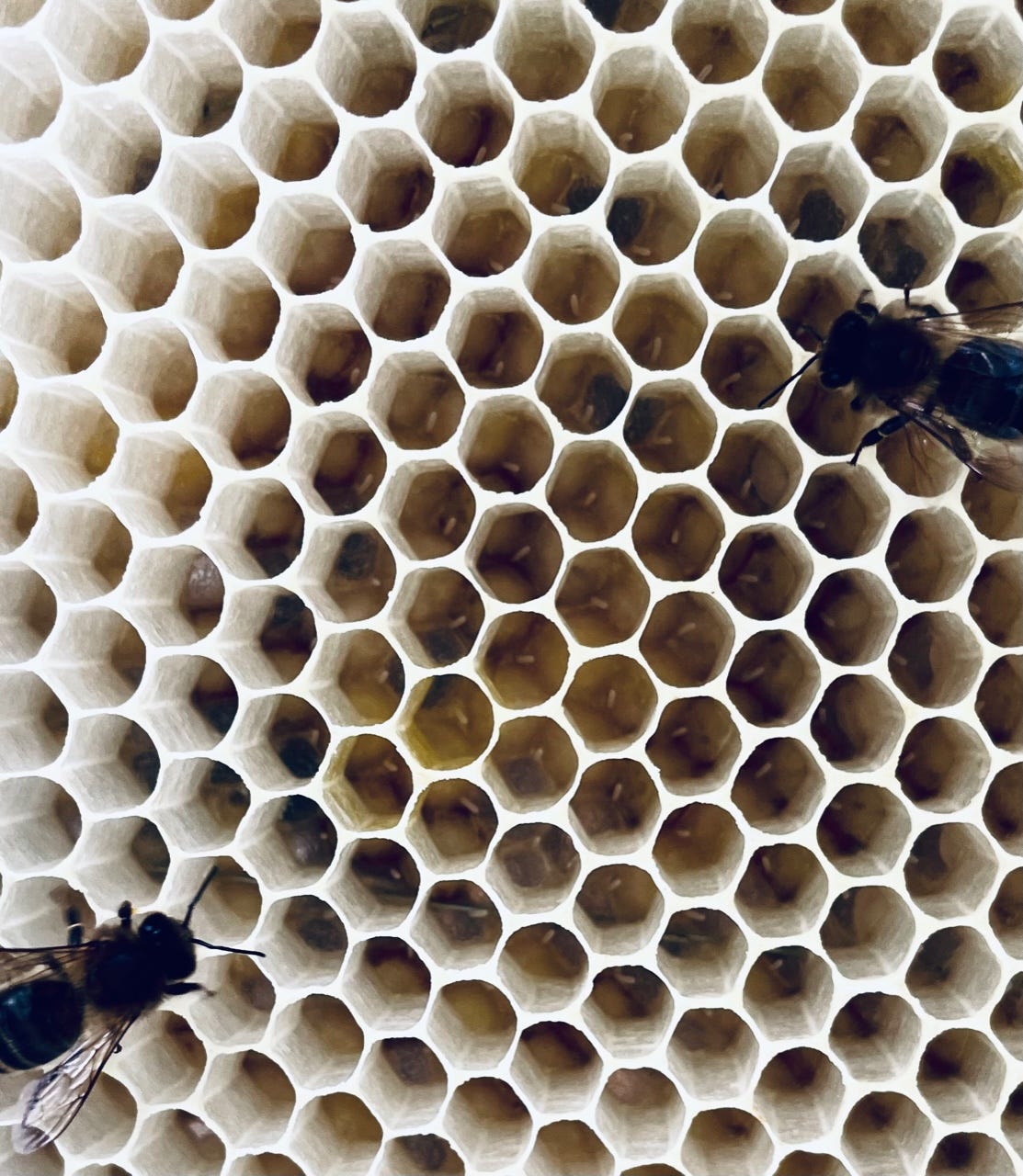

Yesterday, when I raised a frame to the light and saw the speck of eggs in the comb, I whooped with delight. I imagined the secret lives of honeybees whose existence is crucial for our survival. Where was I when the queen dodged birds foraging for their chicks? Or when she timed her flight ‘just so’ to avoid the rain, strong winds and the gathering dark? The little white eggs are a miracle; if hope had a shape, if would be hexagonal.

Kindred

Beekeepers in seventh century Ireland were bound by the Bechbretha, ancient beekeeping laws upheld by the Brehons. Bechbretha was part of the law of comaithches (neighbourhood), under which locals were responsible for the impact of their farming on the four properties closest to them. The families made preliminary pledges to the collective to pay compensation for a wide range of offenses, if incurred.

Under these laws, my three-year immunity as a new beekeeper would be over, and my neighbours would be eligible to receive a swarm. I checked with them; they’re happier to receive honey.

The Bechbretha was progressive, it recognised equality of gender and favoured restitution rather than punishment. It was also inclusive, the families to whom I would have foresworn a pledge were my ‘kindred’. At the heart of the Bechbretha was the desire that the community would thrive. This same desire is present in a hive.

//

What is mine to do? There are so many calls to action in response to the horrors in the world. At night, my heart is so heavy it pins me to the bed. This is appropriate, to wear the sadness like it is mine, because my ability to thrive depends on the health of the collective and some of her is sick.

//

Hum

An old beekeeper told me he could hear when a hive wasn’t right. Since then, I have been listening.

Press play and hear for yourself.

I have three hives. My mother hive, the newly-housed swarm and a third. My mother hive, when I lift the lid, is pitch-perfect and resonant. Their wings beat in the key of C, a melodic frequency that instantly brings calm. I join in, raising my voice in prayer for all I don’t understand and cannot change.

My third hive was weak going into winter and it is a marvel it survived. It emits a sound that puts my nerves on edge. It has a queen, but the workers are not content. I am taking my time with this colony. I give ear to their woes, I feed them when they are hungry, I tell them we are all in this together.

Map-making

‘Telling the bees’ is an age-old practice. When I talk, sing or dance with my sisters, I am entering a tradition of beekeepers who find healing in a hive. There, a bee tells her friends where to find strawberry clover at the lakeside. She dances a meticulous map on the capped honey and everyone pays attention. Here, a nurse bee mixes pollen and royal jelly for larvae. At the entrance, guard bees intercept a wasp and make short work of him. They’re all around me, exploring my gloves, flying against the mesh on my face for a better look, listening closely to the stories I tell.

But this is not a one way street, it is a conversation.

According to ancient lore, honeybees are messengers from the gods to teach us how to live: in sweetness, beauty and peacefulness.

Sweetness.

Beauty.

Peacefulness.

Can you help me spread the word?

Note on image - The Hexagon Project is a non-profit organisation that uses the Hexagon as a metaphor for interdependence and interconnection. The hexagon represents complex relationships and interdependent lines, like the bonds of human connection. It maintains its own presence as a shape and a symbol of light and life. Destined to be part of a whole – it becomes a splendid architectural element, forever expandable. Multiples attach and strengthen one another to become an infinite network of connections.

How a bee is fed determines what she becomes. I love this line. I am also fascinating by that idea of listening to the hive to hear if it isn’t right.

What a wonderful post! How ignorant most of us are about the natural lessons all around us. Your bees are blessed to have such a devoted dancing mother. Looking forward to the honey!