Stir it up

The wisdom of fruitcake.

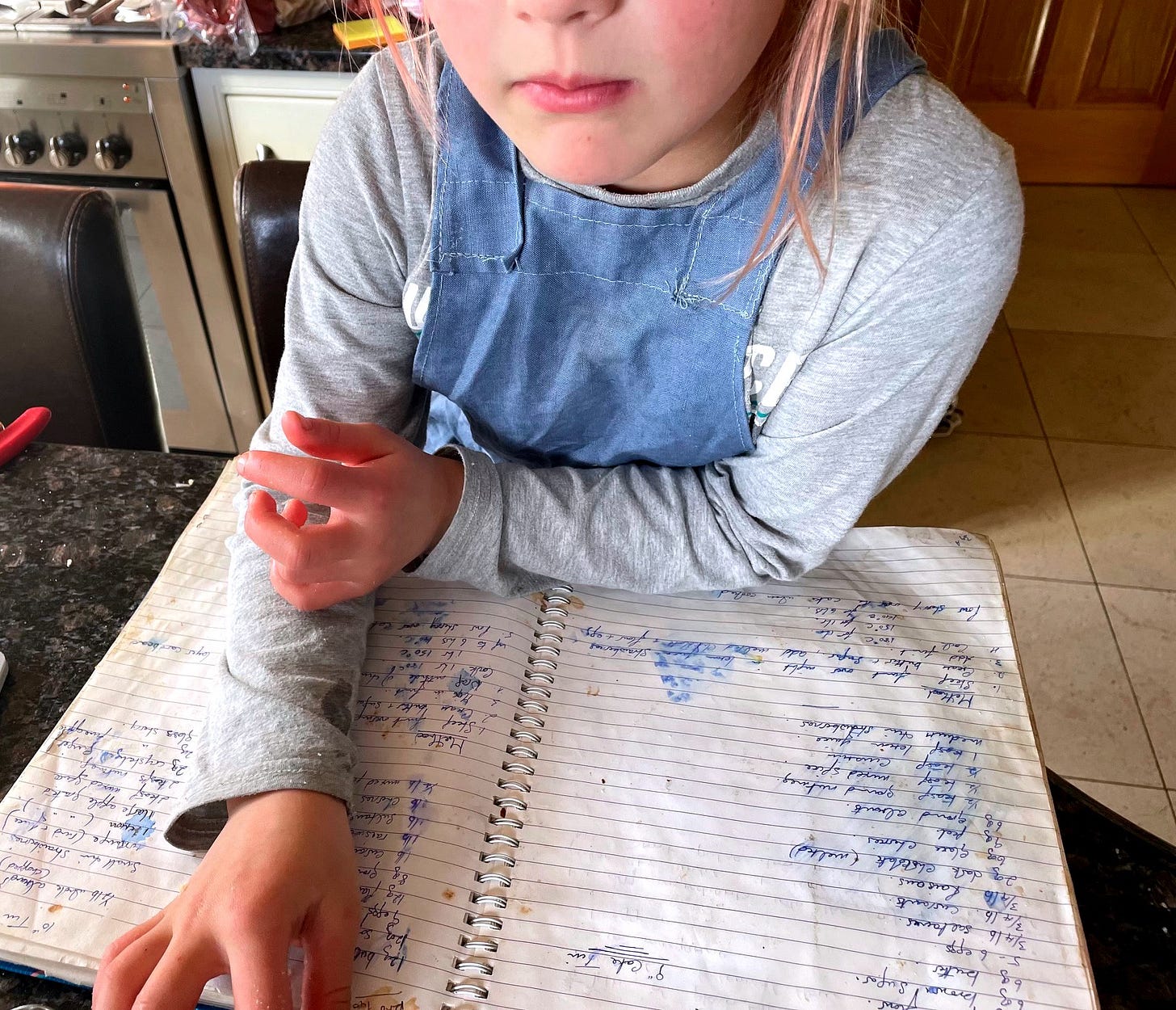

It is November and we are gathered to speak the language of soft brown sugar, crystallised ginger, mixed spice and sherry, while the AGA wheezes in the background like it’s catching its breath. The recipe is entitled ‘My Christmas Cake’ and the ingredients are barely legible. Every year we erase a little more of the ink penned by my grandmother-in-law while preserving something of her memory in the form of a nutty, boozy fruitcake.

This time eight years ago I learnt how to cream. It is a stage in most cake recipes and I believed I understood it well. When I brought the bowl to my mother-in-law, however, she rubbed butter between her fingers, felt the grit and told me to keep going. It takes time. Creaming is to work sugar evenly throughout the batter and incorporate air. Every granule needs to find its place. Now, when I cream, I am patient. I pause mixing to scrape down the bowl. I wait for its transformation into pale clouds, the sugar suspended like rain.

While I cream my daughter blanches almonds. I asked my mother-in-law why we could not buy ground nuts. She said she liked to have every ingredient in its raw form without cutting corners - you can taste her commitment in the cake. Boiling water is poured onto whole almonds and when it cools my daughter strips them of their brown jackets. She gives me some to work on. This too takes time. My attention is on my hands and the slip of wet skin between my fingers. There are tiny ridges on an almond where vascular bundles once delivered water and food to the developing seed. I read them like braille - hot, dry weather; a confetti of blossom for the bees; pods ripening like peaches in the sun.

Paying attention

My friend Ciara wrote this week about collecting cowrie shells on the beach: ‘Before I was aware of such concepts as mindfulness and grounding I think this was my version, doing something while doing nothing, a kind of active relaxation.’ It is the art of paying complete, undivided attention to the present moment and accepting it as the only thing that truly exists. The almond then becomes the most marvellous thing to behold. Ancient seed. Nutritional powerhouse. Skin-pale and soft when blanched, like the underside of a wrist. Utterly vulnerable.

We bring bowls of brandy-steeped fruit in from the utility room. Raisins, sultanas and currants have rehydrated overnight, their bellies round and soft. We add tinned pineapple, mixed peel and bright pink glacé cherries. The smell of spice - cinnamon, fresh nutmeg, ground cloves - takes me back: school concerts as narrator of the nativity story, the Christmas Market in Budapest and the Glühwein I drank in Lesotho after a harrowing, icy drive on the Sani Pass switchbacks.

I add egg to my creamed butter. Slowly - I don’t want it to curdle. Curdling is a shock response when fat in the butter cannot hold liquid from the egg. If the egg is too cold or added too fast, it destabilises the batter and separation occurs; the magic of emulsion - combining things that do not mix well - is lost. I do not leave my post. I add egg a spoonful at a time so the opposing ingredients can ease into one another’s company.

Baking by heart

Four generations of women work together on the cake. My great-grandmother-in-law hand-wrote the recipe. She baked her Christmas cake while turkeys fattened in the yard and weeks of slaughter and pluck lay ahead. My mother-in-law was raised on her soda farls, boiled cake and tart. She bakes instinctively - weighing ingredients by eye, whipping up pancakes for the children while my back is turned. I try my hand at most things in the kitchen and have known both spectacular failure and great success. In the newborn years, when I couldn’t write, I channelled my creativity into food. We ate soufflés on a Tuesday, daily fresh bread and whatever took our fancy when many hands needed light work. Once, I tried quiche for a dinner party. With half an hour to spare, and two children under two needing fed, I poured a litre of eggy mixture into a pastry case. It escaped through a hole onto the kitchen floor leaving the bacon bits behind. We phoned for takeaway. Lastly, my daughter, a firecracker free spirit. She bakes sticky toffee pudding with her friend for the school market and makes a killing every term. Egg-cracker, knife-wielder, almond-blancher - she’s a natural.

We meet at the island with batter, ground nuts and fruit. When everything is emptied into the Mason Cash mixing bowl, we don our gloves and get stuck in. It oozes between our fingers, little pockets of flour bursting like blisters. We assess it for moisture and add orange juice accordingly. Mammy always mixed it by hand. And like that, wisdom is passed down the generations. Embodied wisdom from my great grandmother-in-law who was widowed twice, raised a rabble of children and took refugees in during the war. Who had hectic busy days but stood wrist-deep in cake batter every Christmas. Who passed on a deep love and appreciation for baking and whose recipes I consult weekly.

My daughter sticks her face into the bowl and inhales. I can only hope she continues this ritual or picks it up down the line like a dropped stitch. Hers is a world hurtling to its conclusion. If I can embed this scent in her limbic system where memory and emotion are seated, perhaps it will remind her who she comes from. She is outgrowing our scaffolding so fast, throwing up walls, elaborate porticos, labyrinthine basements with great flair. These cake-making days underpin it all. The substratum upon which a life is built, can fall and be rebuilt again.

The aroma of winter

The cake tin is encased in cardboard before baking. This allows it to be in the AGA for six hours without burning. We stay close to it all evening, checking the thermometer then loading the top plates with cauldrons of water to lower the temperature. Every check releases a breath of scorched cardboard and spice; like kiln-dried birch or a raku pit when the pottery is unburied. It’s what intimacy with my mother-in-law smells like, afternoons of drifting in and out of conversation, forever interrupted by requests for water, spare batteries and snacks. It is the aroma of winter, dark beginnings, the scent of the crucible being lit.

I keep the cake in my bedroom cupboard, a rich dark slab wrapped in parchment paper like a gift. When it is hungry I feed it brandy and the alcohol dribbles into the cracks and soaks the sponge. In a few weeks we will cover the scorched raisins in a layer of warm apricot jam, a sheet of marzipan and fondant icing. We’ll dig out the little penguins that have adorned our cake for years and I’ll get a photo before we tuck in. Only then will I see whether I creamed the butter sufficiently, whether the fruit sank (too much liquid) and if I laced it with enough brandy. I do not, in fact, eat Christmas cake so my entire labour is one of love - for my mother-in-law, her mother, my daughter, the feeling of batter in my hands and my husband who eats it every day until it is finished.

PS: If any of you lovely subscribers are interested in baking our Christmas cake recipe, send me a note and I will pass it on. My great grandmother-in-law would like that.

A delicious piece, Bethany. How blessed you are to have such a mother-in-law. And daughter! I’m looking forward to a wee taste!

Absolutely beautiful Beth, love the imagery and all the smells you’ve easily conjured of a day well spent doing something gorgeous. You need to work on liking Christmas cake! Delicious with a bit of blue cheese and a glass of port. X