He is dressed to kill: hiking boots, camouflage fleece and a pair of multi-pocketed trousers from which things bulge - lifestraw, whittling knife, a couple of chocolate rice cakes. He measures flour into a Tupperware, then leaves two white handprints on the seat of his trousers. Over his shoulder, my husband pours buttermilk into the box and tells him to give it a good knead. Together they pack the Kelly Kettle, fire steel and several bubble-wrapped eggs into a backpack.

“Don’t forget to tell school I’m having a bushcraft day,” he shouts on his way out the door.

~

It is, perhaps, a little strange to begin an article about the Sudbury School with a story about non-attendance. But here’s the thing - so many of the questions I am asked about self-directed education feel back to front.

For example, I was recently quizzed about what happens if Sudbury students do not choose to study maths. (This is a surprisingly common question. My hunch is that adults know, that if given the choice, many children would skip maths as it is presented in its current form.1) I told the questioner that children in a self-directed learning environment do not have to study anything they don’t want to. She was horrified. How would they know how to add?

I went on to give a case study. My eldest, who consistently struggled with maths when we home educated, developed a narrative that he was bad at the subject. We never talked about learning in terms of subjects, nor did we do a lot of maths out of context. We integrated mathematical concepts into whatever we were doing: baking, woodworking, geography and, most importantly for him, music. Yet he still told people he was ‘bad’ at maths. This school year, he has attended two maths classes a week. He can stop at any time. No one forces him to be there. He hasn’t missed a single one since September.

What do you want?

The underpinning belief that fuels self-directed education is that children want to learn. They are curious, motivated people with brains fizzing with creativity. They want to make sense of the world around them, and figure out what they love. If left to their own devices, they choose to learn. It may not look the way we think it should, but the main difference between it and mainstream education is that it comes from the inside out, not the top down.

~

So, they just do whatever they want?

Yes.

In the Sudbury School they spend their days however they please. At 10.30am they all attend Morning Circle, an opportunity for the community to discuss plans for that day, available classes and requests from students. After that, they disperse, some to book a slot in the music room, others to play Czech dodgeball, some to attend maths/science/cookery/English or whatever classes are on that day.

If there are disputes, they are taken to the Justice Committee (or Just Chat as it has been renamed), a staff and child facilitated conversation to seek resolution. When the children have new ideas of things they would like to learn, they make a proposal at School Meeting. Involvement in the school’s democratic processes is central to their learning.

My daughter spends hours creating elaborate Sylvanian Family set ups in the play room. I tried to pep talk her over Christmas about joining some classes and thinking more seriously about her education (I have regular wobbles like these). You can’t get a job playing Sylvanians, I may have said. She was furious.

“I’m not ready to stop playing,” she told me, through her tears.

She has watched her brother leave the land of make believe and not return - she knows her time will come. I apologised, then mastered the art of sewing tiny Sylvanian-shaped sleeping bags from fabric scraps. I’m all in.

~

What’s the rush?

Before he left the house, my youngest packed a book in his backpack. He is eight and has only recently become a fluent reader. This is another topic about which I have been asked many questions.

The first home education meet up I attended was at a swimming pool in Belfast. My then five-year-old and three-year-old were to have an informal lesson and the mums could chat in the bleachers. My five-year-old struggled to walk the 50 metres to the swimming pool edge without me, a crisis in confidence caused by his two brief months in primary school. The heat was unbearable, there were babies crawling everywhere, including my five-month-old, and mothers passing around tins of gluten-free goodies. I admitted to a few of them that I was terrified. They nodded and smiled, been there, felt that. I whispered to one that my son could not read. He’s only little, she said. What’s the rush? I will never forget that conversation - it steadied me through many years of reading reluctance until the cogs aligned and the words made sense to him. It has helped me afford the same patience to my youngest who showed no interest in reading, until he did. Now, we make weekly library trips to keep pace with his appetite.

I am not entirely sure how my three children learned to read. My focus was raising children who loved literature by reading aloud to them daily. We read everything from history books to science fiction, poetry and plays, the classics and works of non-fiction. I packed as many books into their early years as I could. Because now, they choose their own! I have a 12, 11 and eight-year-old who love to read. Each one of them discovered the key to unlock words and sentences at a different age, in their own unique way. Yet another one of life’s mysteries.

What if…

I am grateful for how this taught me to trust, and trust some more. Because every stage of their education presents me with another, What if… set of questions, and I am determined not to respond to these unknowns from a place of fear. Here are a few I am fielding at the moment:

What if they don’t want to do exams?

What if they finish school with no qualifications?

I adhere to Rilke’s philosophy on questions:

‘…try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don't search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.’

I am not, of course, alone in this. Whatever learning environments we choose for our children, we are making a choice, and it will come with many unknowns. We moved our family more than 100 miles from our friends and family because the Sligo Sudbury School aligns with many of our core values. It was a high stakes choice. One of my darling children, when doing a recap of his first term, told us one of their lows was our walking holiday in Portugal. I bit my tongue and allowed my even-tempered husband to ask some follow up questions.

“How come?” my husband said.

“Because I missed out on a week of school.”

They love it. They are part of a community that honours their choices, and supports them to pursue their passions. It is not always a perfect environment (is there such a thing?), and we have had many challenges as the children have sought to find their place, but they love to be there, and that speaks for itself.

~

When the bushcrafters return, my son is wielding a hazel spear and is delighted to report having lit the fire with nothing but his steel and a bit of birch bark. He disappears off to his bedroom to build lego and I watch his introverted tank fill to the brim. He loves school too, he just chooses to stay at home every so often because it is a lot. Does this show a lack of commitment or an inability to see things through? No. It shows a knowledge of self and the ability to ask for what he needs, something, I think, many of us have to relearn later in life.

What now?

My Sudbury education has been learning to come alongside. I am there to transport instruments to gigs and support mini-chefs baking cakes for the school market. I offer my skills to the wider community, teaching writing classes and helping out where I can. This summer we’ll be supporting Pizza Island, a fundraising initiative my daughter signed us up to. We’ll be ferrying children to an island to camp out and eat pizza! Our school gets no government support. It relies on the investment of those who share the vision for alternative education; it depends on the community of families it serves.

If you want to learn more about the Sligo Sudbury School and it’s incredible plans for a new school building to showcase the self-directed learning model in Ireland, go here.

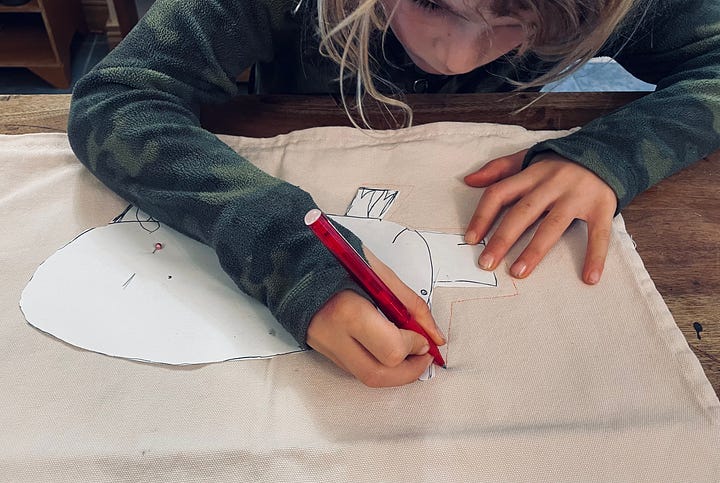

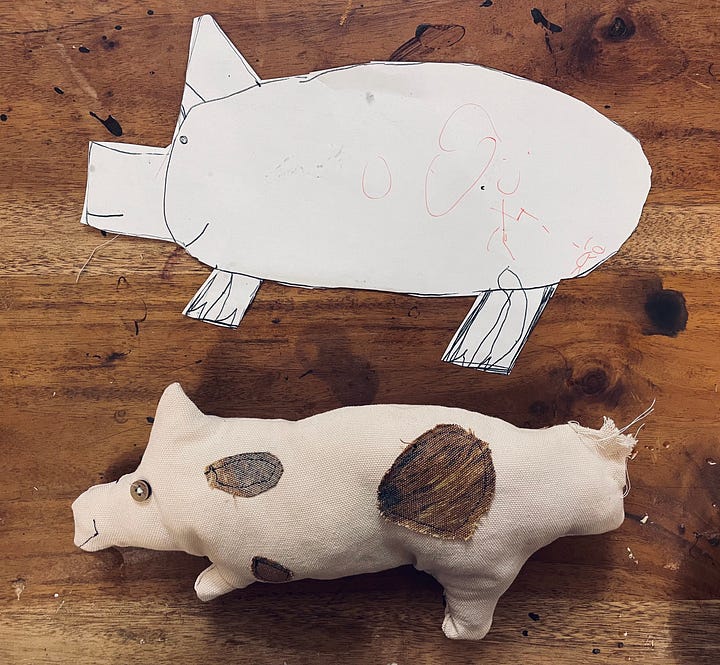

In the meantime, my eight-year-old is chomping at the bit to turn the two dimensional pig he has drawn into a hand-sewn toy; there’s nothing in the world I would rather do.

This post was written in response to readers’ requests for insight into self-directed education. Do you have any questions or comments? Please get in touch, I’d love to hear from you (even if you completely disagree).

There are, of course, exceptions to this. My sister is a maths genius and excellent educator and I mean no disrespect to those who work in this profession. I also, ironically, loved maths in school!

The wee pig made me cry! Lovely photo of your gorgeous nature warrior. I now understand why Edith doesn’t want to give up play. Once you let it go it’s hard to get it back. Great informative piece from a brave and wonderful pioneer.

Loved reading this! We lived in Sligo when my boy was small and if we'd stayed I think that's where he'd have gone. I still wonder where he'll go to secondary as there's no educate together secondary in Mayo. Some parents I know have mentioned the idea of driving to Sligo for secondary!